A key aim of this essay is to aid directors in developing a robust visual design process. By doing so, it seeks to prevent the wastage of limited resources and time, helping directors to work more efficiently and effectively in bringing their vision to life on screen.

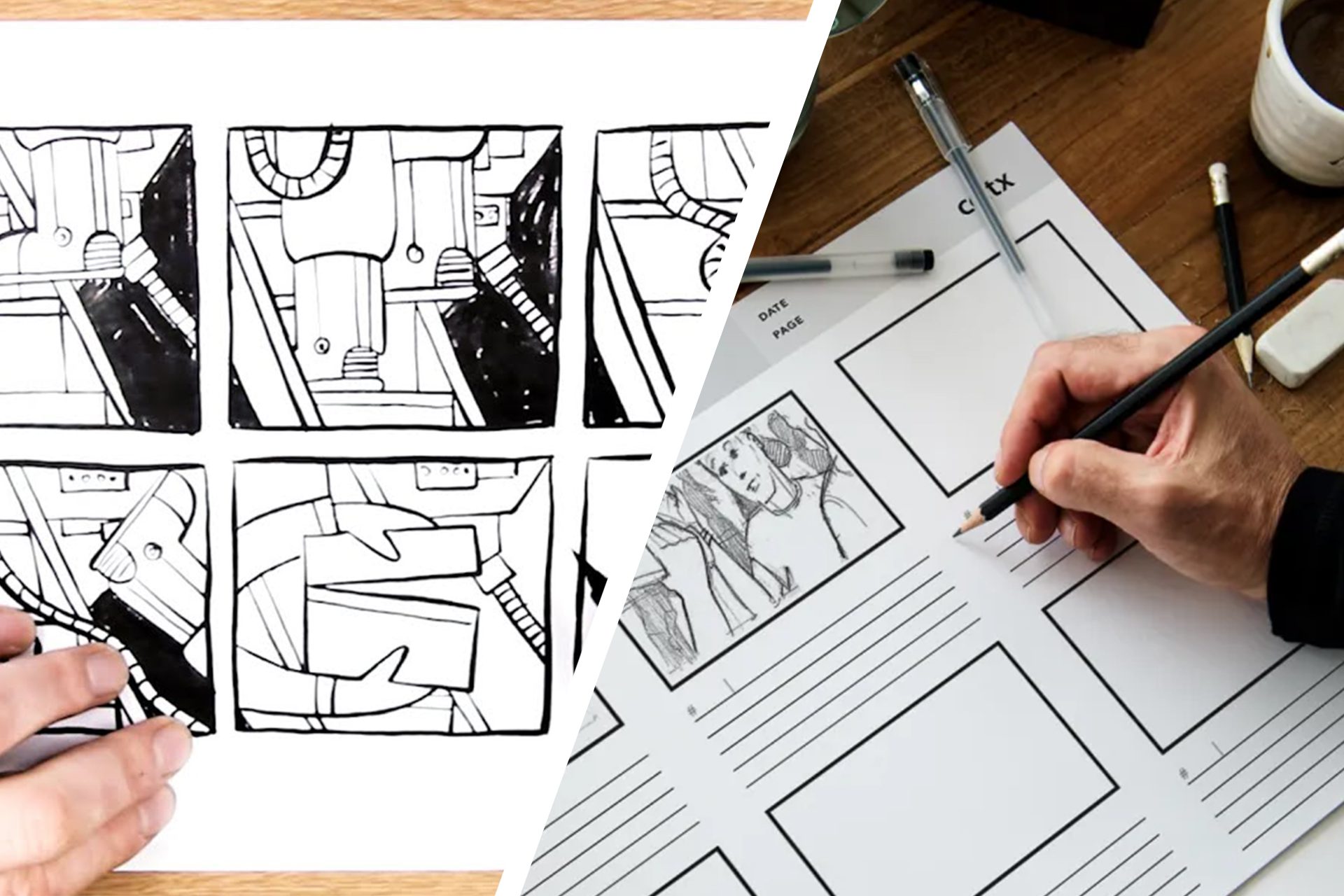

Maurice Zuberano, a highly respected production illustrator and art director, famously referred to the storyboard as the “diary of the film.” This metaphor captures the essence of storyboards as a pre-visualization tool for future events in filmmaking. Zuberano’s description emphasizes the storyboard’s role as a private record of the visualization process, which is often why few storyboards remain intact after a film’s production. These illustrations serve as tangible evidence that the visual conception of a film frequently involves contributions beyond the director’s vision. For directors lacking a strong visual sense, the storyboard illustrator becomes crucial, acting as the shot-flow designer responsible for structuring, staging, and composing shots and sequences.

There are, however, directors with a profound visual acumen who utilize storyboards not just as a tool but as an integral part of their creative process. Alfred Hitchcock, perhaps more than any other director, epitomizes this approach. Renowned for his meticulous use of storyboards, Hitchcock leveraged them to refine his vision and maintain control over the filmmaking process, ensuring his original intentions were faithfully translated to the screen. Starting his career as an art director, Hitchcock used storyboards to assert his creative influence over the visual design of his films. He often claimed that his movies were completed in his mind long before filming began, a statement supported by his rare use of the camera viewfinder on set, as he relied on the approved storyboard as the definitive guide.

Hitchcock’s methodology left a significant impact on the next generation of filmmakers in the 1960s, who grew up with a burgeoning appreciation for continuity graphics in comics, which were gaining recognition as a legitimate American art form. Among these filmmakers, Steven Spielberg stands out as the preeminent visualizer of entertainment cinema. Spielberg, influenced by Hitchcock and his own collaborations with George Lucas, has published collections of production art, highlighting the importance of storyboards and production illustrations. Storyboards have been indispensable in achieving the intricate staging and dynamic effects characteristic of Spielberg’s work, and their meticulous polish has set a standard for many aspiring filmmakers.

While some may argue that the modern emphasis on storyboarding reflects a lack of depth in today’s Hollywood filmmakers, suggesting they rely heavily on comic book-like visuals and action sequences, the reality is quite different. Storyboarding is a valuable tool used across a wide range of films, regardless of their subject matter. In fact, films with less action might benefit even more from storyboards than their high-octane counterparts. Even a director like Jean-Luc Godard, known for rejecting traditional storytelling techniques, occasionally used storyboards to plan out the flow between shots.

The primary functions of storyboards are twofold. Firstly, they enable filmmakers to visualize and refine their ideas, similar to how writers develop their narratives through multiple drafts. Secondly, they provide a clear and effective way to communicate these ideas to the production team. As productions grow more complex, the importance of this communication tool increases, but storyboards are not confined to action-heavy or big-budget films. Even smaller, more intimate dramas can benefit from the clarity and direction that storyboards provide, helping directors to hone their storytelling.

The Collaborative Process of Storyboarding

Every film is a unique blend of talents and personalities, and the responsibility for the visual style is shared among the production designer, director, cinematographer, and editor. Recently, there has been a trend for directors to collaborate directly with sketch artists, transferring some continuity responsibilities from the production designer to the director. Despite the highly decentralized production system of today’s major studios, a visually oriented director has always been able to control a film’s look. With the decline of studio-imposed house styles, directors have become the primary decision-makers regarding the visual and thematic elements of their movies.

Directors with a background in graphic arts or a talent for drawing, such as Alfred Hitchcock and Ridley Scott, often create rough storyboards themselves, which are then refined by a storyboard artist. For instance, Sherman Labby worked with Ridley Scott on the film “Blade Runner,” receiving evocative line drawings from Scott, known as “Ridleygrams.” These sketches provided a visual foundation for many scenes. This practice is not limited to Hitchcock and Scott; other directors like Eisenstein, Fellini, and Kurosawa have also storyboarded sequences or contributed detailed conceptual sketches to their films.

Even directors without significant drafting skills, such as Steven Spielberg and George Miller, sometimes produce simple stick-figure drawings to convey specific compositions or staging ideas. Regardless of the director’s drawing ability, the storyboard artist plays a crucial role in contributing ideas and enhancing the director’s vision. This collaborative process ensures that the final visual style of the film is a product of combined creative efforts, ultimately resulting in a cohesive and visually compelling narrative.

Paul Power, a production illustrator with experience in both comics and film, thrives on collaborating with directors through extensive brainstorming sessions. These sessions often involve reading dialogue and acting out scenes from the script, with the director pausing to make rough sketches. These initial sketches are later refined into detailed drawings for further discussion. Power’s deep involvement in the staging and dramatic concept of a film has led him to describe his work as “acting with a pencil.” He defines the production illustrator’s role as assisting the director in realizing their vision. This emphasis on the director’s vision was a recurring theme among production illustrators. The craft of storyboarding inherently teaches illustrators to be adaptable, as they frequently refine sequences through numerous revisions. Production illustrators understand that multiple solutions exist for any given problem, and the challenge lies in interpreting the director’s perspective of the script.

A unique example of collaboration between storyboard artists and directors is the relationship between production illustrator J. Todd Anderson and the Coen Brothers. Anderson has storyboarded all the Coen Brothers’ films since their second movie, Raising Arizona, in 1987. Their collaborative process is straightforward yet effective. They work through one scene at a time, acting out the staging. Joel, the director, has a specific shot list, and Ethan may have rough sketches. As they pitch the scene, Anderson quickly draws loose thumbnail panels, capturing the action with stick figures and shapes in just a few seconds. Notes and arrows indicate motion, and the primary details of each shot are written down during the process. Anderson memorizes the Brothers’ intent and spends the rest of the day developing the quick sketches into more detailed panels. These are reviewed the next day, where they are either approved or revised. This iterative process can require multiple passes of a sequence and typically continues for six to eight weeks, ensuring that every scene and setup in the movie is represented in the storyboard.

The end result is a comprehensive illustrated script, with one page of panels corresponding to each page of the script. These storyboards are shared with the cast and crew, providing a clear visual reference for the entire production team and ensuring everyone understands the intended look and flow of the film. This meticulous approach helps to streamline the filmmaking process, aligning the team’s efforts towards a cohesive final product.

The Timeline and Challenges of Storyboarding

The time that production illustrators spend on a film varies widely, influenced by the complexity of the production and the specific needs of the director. While it’s difficult to establish an average timeline, thoroughly storyboarding an entire film, rather than just select action sequences, typically requires a minimum of 4–6 months. The level of detail in the drawings significantly impacts this timeframe. Large productions with intricate sets and effects often necessitate the involvement of multiple sketch artists. In some cases, the production designer may also contribute continuity sketches. Even with a team of artists, storyboarding a complex film can take up to a year. This extended schedule often reflects not just the drawing time but also the numerous revisions, script changes, and the director’s decision-making process.

The term “look development” or “look dev” refers to the period when the director and art department work together to identify the film’s visual theme. Directors vary in their approach to this process. Some directors possess a clear visual sense and make swift, decisive choices, while others need to explore numerous options, potentially leading to indecision. This indecisiveness can be costly in terms of both time and resources. The industry distinguishes between “selectors” and “directors”: selectors need to see every element multiple times and often lack clear or consistent recommendations, whereas directors have a well-defined vision and can explain their decisions coherently.

The Skills and Demands of a Production Illustrator

A production illustrator must possess a deep understanding of staging, editing, and composition, as well as a comprehensive knowledge of lens use in cinematography. They must be proficient draftsmen, capable of drawing the human figure in a variety of poses without relying on models or photographs. This skill is crucial, as it allows for quick, accurate illustrations under the pressure of tight deadlines. Furthermore, production illustrators need the versatility to adapt their work to reflect different historical periods and exotic locations, even if they are not inherently familiar with them.

While extensive research is often necessary, a production illustrator is not expected to have an encyclopedic knowledge of period-specific details or obscure settings, such as the interior of a German submarine or the skyline of Nepal. However, a strong visual memory is invaluable, enabling the illustrator to quickly gather and reference the necessary material to create accurate and convincing sketches. This ability to work efficiently and effectively under pressure is essential in the fast-paced environment of film production.

In addition to technical skills and adaptability, the illustrator’s role demands a high level of creativity and problem-solving. They must interpret and visualize the director’s vision, often with limited guidance and changing requirements. This requires not only artistic talent but also the ability to think on their feet and make swift adjustments as needed. The combination of these skills ensures that production illustrators can contribute significantly to the visual storytelling process, bringing the director’s ideas to life through their detailed and dynamic sketches.

The Modern Era of Storyboarding and Concept Art

The liberal use of storyboards and elaborate concept art in today’s film industry is largely driven by the prevalence of superhero films and visual effects–heavy productions, many of which have budgets exceeding $150 million. Given that many of these films are based on graphic novels or comic books, it’s unsurprising that we are experiencing a renaissance in production art. Concept artists like Craig Mullins and Doug Chiang spearheaded this movement, followed by a surge of digital artists who now showcase their portfolios online. These modern artists often possess skills in photography, 3D modeling, and traditional art materials, reflecting the diverse demands of contemporary filmmaking.

Today’s typical storyboard artist works in a highly digital environment, often equipped with dual 27-inch monitors and a Wacom tablet, likely a Cintiq. They frequently use the internet to research and download hundreds of images, incorporating parts or entire images into compositions painted in Photoshop. Skilled in 3D software like Maya, they regularly download 3D models from resources such as TurboSquid or Renderosity, integrating these elements into layered Photoshop files. This blend of photography, 3D models, and painted elements has significantly influenced modern illustration styles, making the transition between traditional and digital mediums seamless.

Storyboard artists in studio productions are also adept at creating presentations using software like PowerPoint, often enhancing these with visual and sound effects in Adobe After Effects. Adding sound and limited effects to edited storyboards greatly improves their impact, creating a more immersive and compelling presentation. The availability of extensive online libraries of images, sounds, and effects presets further simplifies this process.

The advent of tablets like the iPad and its competitors has also revolutionized the way storyboards are presented. These devices offer vibrant, backlit displays that enhance the visual appeal of storyboard sequences, making them more effective than printed images. This digital shift has streamlined the workflow of storyboard artists, allowing for more dynamic and visually rich presentations that align with the high standards of modern filmmaking.

Overcoming the Limitations of Storyboarding

The most apparent limitation of storyboarding is its inability to convey motion, not just the action within the frame but also the movement of the camera. Traditional storyboards also struggle to represent optical effects such as dissolves and fades, as well as manipulations of depth of field and focus. However, digital drawing tools offer some solutions. For instance, artists can blur parts of an image to simulate depth of field. To indicate motion within a static storyboard frame, artists often use arrows, captions, and schematic drawings in the margins. A schematic might include a top view of the set, showing the camera position and angle of view. Additionally, techniques from animation, such as using sequential frames to depict movement, can be adapted for live-action storyboarding.

While the storyboard frame outlines the camera’s viewpoint, it can sometimes be beneficial to show what lies outside the frame. Many artists start their drawings without frame lines, sketching the scene’s basic elements first. Once they have a clear picture of the scene, they choose the best shot and draw the frame around it. In traditional storyboarding, artists might use cardboard panels with different frame sizes to select a shot, whereas in digital formats, the frame can be placed on a separate layer in programs like Photoshop.

Despite the advantages of digital tools, the tactile experience of drawing with pencil on paper remains unmatched by input devices. Affordable inkjet printers and password-protected sites for sharing high-resolution artwork and video offer various ways to present and share production art. Most work is shared online today, with many presentations viewed on laptop screens. When illustrations are printed, it’s often for presentations to investors, distributors, or studio heads.

During preproduction, storyboards are distributed across various departments. The presentation format depends on their intended use. In animation, following Disney’s model, storyboards are often displayed on walls or bulletin boards in the art department, allowing for a comprehensive view during group meetings. While this method is useful for logistical planning, it is less convenient for visualizing precise shot-to-shot flow and timing. Early in the storyboarding process, directors might create beat boards to sketch out the entire movie quickly. These rough sketches represent significant story beats and are typically pinned to walls for continuous revision. Over a few weeks, hundreds of sketches might map out a 90-minute film. Subsequent revisions refine key dramatic moments and turning points.

The storyboard process involves constant collaboration and refinement. Editors cut beat panels into sequences and acts, often using a scratch track for preliminary editing. This process continues with increasing detail until a 90-minute beat movie emerges. At this point, the storyboard team and editors collaborate to add limited animation, creating a previs (pre-visualization) version of the movie. This animated storyboard version is crucial for assessing the story’s effectiveness before full production begins.

In animation, achieving a previs version of the movie is the ultimate goal of storyboarding. This allows the team to present a rough version of the film to an audience, gauging reactions and making necessary adjustments. The iterative process of storyboarding, with its numerous revisions and refinements, ensures that the final product closely aligns with the director’s vision, providing a strong foundation for the production.

The Dual Role of Storyboards in Filmmaking

Storyboards essentially convey two types of information: a description of the physical environment (set design and location) and the spatial qualities of a sequence (staging, camera angles, lens choices, and the movement of elements within the shot). While a storyboard illustrator is responsible for conveying mood, lighting, and other environmental aspects, the director primarily focuses on showing the basic camera setup and the placement of subjects. This can be effectively communicated through simple drawing styles or diagrams.

One of the most important points to understand is that storyboards are beneficial to the director, whether they are followed meticulously during shooting or not. Once significant portions of the script are storyboarded, the director can visualize the dramatic flow of the story in a way that the screenplay alone cannot reveal. Moreover, the act of visualizing scenes on paper helps generate new ideas, not just establish a plan for the production team. This process is even more valuable when the director creates their own drawings. Engaging directly with images, regardless of the drawing’s simplicity, helps directors refine their vision. For example, director Brian De Palma used to draw his own stick-figure illustrations on a Macintosh computer with the now-defunct software Storyboarder®. Though basic, these drawings likely served as mnemonic devices, with each frame representing a detailed shot in De Palma’s mind.

However, different directors may find various methods of representation that suit their needs better. One of the pleasures of studying storyboards is discovering the unique approaches each illustrator takes. If you can draw, there’s no reason not to create more detailed storyboards. While it’s beyond the scope of this discussion to teach drawing skills, one critical piece of advice for storyboard artists is that simplicity is key. This concept, often heard among seasoned artists, applies to storyboarding where time constraints rarely allow for highly detailed drawings of every panel.

All storyboards are adaptations of the screenplay, which is an intermediary form designed to be visualized and heard. A screenwriter writes drama intended to be seen and heard, and storyboards help translate these written ideas into visual sequences. In theory, a storyboard artist simply pictorializes the screenplay’s ideas, but in practice, they often refine and enhance these ideas. This can include suggesting literary elements, restructuring scenes, adding story components, and contributing dialogue, making the storyboard a near-final draft of the screenplay.

By understanding the dual role of storyboards in depicting both the physical environment and spatial qualities of a film, and recognizing their value in refining and visualizing the director’s vision, filmmakers can better appreciate and utilize this essential tool.

Training and Union Representation for Production Illustrators

There is an abundance of resources available online for traditional and digital art training. Platforms like YouTube host thousands of free tutorials by artists, many of which direct viewers to subscription-based courses. Numerous online art schools offer courses, with some providing credit or certificate programs. Websites like Udemy offer extensive courses in digital software and specific art or visual-effects skills, such as figure drawing or perspective. Additionally, many traditional art schools now offer online degree programs.

For those interested in storyboard courses, there are fewer options compared to broader digital illustration courses. Animation schools often provide more comprehensive storyboard instruction, as storyboarding is a critical component of animation, whereas in live action, it is less emphasized. Nonetheless, traditional training at fine arts or commercial art schools remains an excellent foundation for production designers, art directors, and production illustrators. These schools often offer courses in advertising art, which include television commercial storyboarding. While foundational drawing and painting skills are crucial, production illustrators must also have a strong understanding of cinematography and editing. Courses in film history, technique, and basic photography are essential to complement strong illustration skills.

This wealth of resources and support systems ensures that aspiring production illustrators have ample opportunities to develop their skills and find representation within the industry.